By 1996, it was becoming increasingly clear that ending the war would require tacit diplomacy and a genuine desire by the Sierra Leone Government and its international allies to negotiate with the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). A key proponent of this theory was Rupert Davies, a Sierra Leonean career diplomat attached to the Sierra Leone High Commission in London, at that time.

In his Case Study undertaken under the ‘Extended Programme in Peace-Making and Preventive Diplomacy’ organized by UNITAR (United Nations Institute for Training and Research), and the International Peace Academy in New York, Davies postulated; ‘The de-facto situation on the ground is that neither the Government nor the RUF can attain total victory in this senseless war against the civilian population. The War could go on forever like a swing of the pendulum, each party taking its turn to gain the upper hand.’

Davies further wrote; ‘It is absolutely unrealistic and over simplistic to imagine that it is possible to achieve sustainable peace without making concessions to the RUF.’

This situation apparently brought Omrie Golley into the conflict, and events leading to the peace process during the latter part of 1995 and early 1996.

Senseless killing of civilians, torching of homes, amputations had become common features of the war with most of the country overtaken by rebel forces. Government forces could not retake swathes of territory occupied by rebel forces, even with the assistance of the British and other sympathetic governments.

In fact, the situation had become so protracted and difficult, that mercenary fighters from South Africa, Mozambique, and other countries who had no knowledge of the terrain where airlifted in to aid the war effort, with no appreciable benefits to the overall military situation on the ground.

The presence of mercenary intervention was especially galling to Golley, as it was with numerous Sierra Leoneans, both in and out of the country.

Writing in the Third World Quarterly ( Vol 20 No 2, pp 319-338, 1999), a Sierra Leonean, David J Francis (now the Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Co-operation, in the current Bio Government), wrote a powerful piece, critically assessing the involvement of private military companies like Sandline International, Executive Outcomes, and the Gurkhas in the war in Sierra Leone, arguing that these companies, in the guise of providing national security, were merely lining their own pockets, thereby accentuating international exploitation, calling it: ‘the new face of corporate neo- colonialism’.

The situation in the country at this time was desperate, with no end in sight. Golley was in London in early November 1995 when he decided, against the wishes of his family, to form an organization called the National Convention for Reconstruction and Development ( NCRD ) to look into the causes of the war, how hostilities could be brought to a speedy conclusion, and to start to map out a new dispensation in Sierra Leone to aid the reconstruction of the country in the aftermath of War.

In order to be able to achieve the objectives of the Think Tank he had formed, he (Golley), had to engage other Sierra Leoneans both in the diaspora, and in country, to brainstorm and work out policies to achieve these objectives.

Central to the principal aim of seeking a cessation of hostilities, and an end to the military conflict, was the need to understand the motives of the RUF. It was essential to find out about this Movement, its leadership, their organizational structures, and most importantly, the reasons why they had taken up arms, with a military conflict unheard of in the history of Sierra Leone.

The next stage of the NCRD plan was to explore avenues with the RUF with a view to having a cessation of hostilities, and a more permanent plan to bringing about a lasting and sustainable peace.

In order to be properly appraised of the situation on the ground and the state of affairs generally in the country, Ambassador Golley thought it necessary to consult with a number of Sierra Leoneans in the diaspora and inside the country, including journalists, politicians government officials and others. This is how he came into contact with individuals like Lans Gberie, Osman Yansaneh, Oluniyi Robbin-Coker, Abbas Bundu, Abdulai Conteh, former president Tejan Kabbah, and the Late Joseph Momoh, among many others.

Ambassador Golley wanted to get the views of as many people as possible, to ascertain their own views about the state of affairs in the country at this time. He also undertook a copious amount of travel engagements, visiting a number of countries in the sub region including the Gambia, Guinea, Liberia and Nigeria, in pursuit of this quest for knowledge.

In undertaking these tours and engaging his fellow countrymen in and out of Sierra Leone, it quickly became apparent to him that very little was known about the RUF who, by this time had taken over large swathes of the country with its guerrilla tactics, and forced abductions. Very little contact had taken place with the RUF in their main strongholds. It did not take long for Ambassador Golley to be convinced that one way or another he had find out about the RUF, who they were, and why they had undertaken a ferocious war against their own people.

The RUF assault on Sierra Rutile which took place in late 1995, with its forced abductions was the catalyst that made up Ambassador Golley’s mind to seek the Movement, and look for ways to bring about peace in the country.

BBC reports about rebel advances throughout the country and the destruction they left behind, was enough to convince him of the dangerous direction the country was headed.

Golley was also particularly drawn to the writings of a UK based Sierra Leonean journalist, Ambrose Ganda. Ganda, an indigene from Serabu in the Bo District founded or co-founded a number of Sierra Leonean newspapers including the Watchman, the New Patriot, the Sierra Leone Report and SLAM. His editorial policy resonated with a common theme: – the defence for justice and equal rights of ordinary Sierra Leoneans.

Ganda once wrote; ‘The welfare and defence of the ordinary citizens of the country, and the articulation of their views as one saw them, since they themselves did not have the means to do so’

Like Golley, Ganda was also personally devastated by the escalation of the conflict and was keen on a negotiated settlement rather than violent means to end it at the expense of ordinary Sierra Leoneans. Ganda died on 10th April 2003 after contracting meningitis.

It was clear that the Tejan Kabbah Government intended to crush the rebellion by any forceful means rather than by a peaceful negotiated settlement. Apparently, as days, weeks, months and years progressed, it turned out that the war was not going to end through military means and a paradigm shift from a military solution to negotiations started to prevail. This was pretty consistent with Golley’s strategy and proposition.

It came to pass that all parties to the conflict including the international community gradually succumbed to the idea of a negotiated settlement of the conflict.

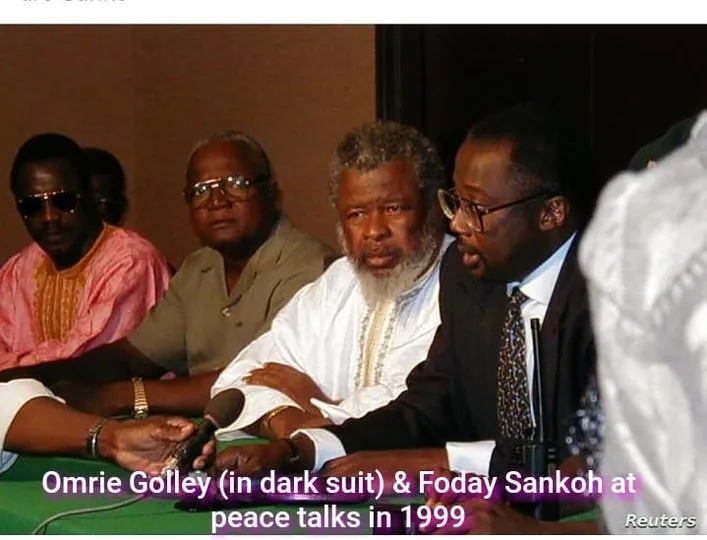

Until 1999, when the Lome Peace Accord was signed, and the subsequent return to Freetown of Corporal Foday Sankoh the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), Ambassador Omrie Golley’s involvement with the RUF was limited in scope and geography to the UK, Nigeria, Togo and Ivory Coast, where he had lobbied regional powers, and placed himself as a Sierra Leonean, unconnected with the erstwhile Government, or the rebels, and deeply committed to an end of the conflict.

Golley’s first physical contact with the RUF was in 1995 when he was accompanied by Oluniyi Robin Coker and Ambrose Ganda to meet four representatives of the Movement in Danane – an Ivorian town that borders the Republic of Liberia. The meeting had been negotiated by the UK based peace building organisation, International Alert, which had alongside the International Red Cross established contacts with the RUF since 1992.

The meeting with the RUF’s representatives at Danane in Northern Ivory Coast, was followed by a request from Corporal Foday Sankoh, to talk to Ambassador Golley through ‘bush radio’.

‘I was obviously very keen to talk to him. In those days they only had bush radio which was a very limited radio communication and they came on only at a certain time and you had to go to one of their safe houses to be able to speak to the bush. I went at the appointed time and that was in early November 1995 to speak to him on the radio for the very first time, and he greeted me very well.’

Golley further explains: “He initiated our conversation with an unexpected question. He asked whether I was the nephew of a certain Inspector Golley, a former police officer in the Sierra Leone Police Force. I said didn’t know who this person was. He then went to tell me that at a very low ebb in his life, this Inspector Golley took him under his wings for a number of years, fed him clothed him, and paid his school fees and that he would always remain grateful to the former police officer”

It wasn’t clear whether Sankoh thought he could make Golley easily relate with him, through this imaginary uncle, or whether the reference, was just one of his several tricks to test the sincerity of the young lawyer.

To this day, Omrie Golley cannot recall having a relative from his paternal side in the Sierra Leone Police Force. In any case, that first radio conversation in Ivory Coast opened the door to the numerous subsequent engagements he had with the Movement.

Members of the RUF delegation at the Ivory Coast meeting included Philip Palmer, Faiya Musa, Deen Jalloh and one Dr Jalloh who used to work at Sierra Rutile. Deen Jalloh was the husband of Agnes Deen Jalloh. Agnes was one of the senior officials in the RUF and a sister of President Julius Maada Bio.

History teaches us that peace is more sustainable when warring parties agree to sit down and talk. From the Second World War, that nearly annihilated Europe and the civil or sectarian conflicts of Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, military conflicts had never been a completely decisive factor at ending these wars.

The Second World War may have ended after the surrender of the axis powers, and the subsequent suicide of Adolf Hitler in May 1945; it however did not take the global powers, Britain, United States, France and Germany, long to recognize the need for a permanent solution to a conflict that literally brought the world to its knees.

The August 1945 Potsdam Agreement that later became the Three Power Conference of Berlin, was probably the climax of several conferences, held to address the root causes of the war and to sign a deal that would lead to a permanent resolution to the conflict.

The United Nations was subsequently established the same year to expand and operationalize global peace security architecture around the world.

It wasn’t clear whether the United Nations officials deployed to Sierra Leone were oblivious of this historical perspective, or had read Ambassador Golley’s script. What was clear however, was the fact that almost every UN official deployed to Sierra Leone during the civil conflict had tapped on, and invariably benefitted from the diplomatic and negotiation skills of this gentleman, from 1995 onwards.

That telephone conversation at a safe house in Danane, Ivory Coast with Corporal Foday Sankoh, was to become the foundation, upon which Omrie Golley’s role in the peace process was built. It was through that safe house bush radio conversation, that Golley was able to detect an uncanny desire for international recognition and acceptance, from the RUF leader.

The formation of an external delegation by the RUF, was no small measure an attempt to establish diplomatic contact with the outside world, and it had become obvious that the RUF leadership wanted to be taken seriously.

Ambassador Golley met Foday Sankoh for the first time, on the 24th March, 1996, in the City of Yamassoukro, Ivory Coast, 450 kilometres north of Abidjan. This was a couple of months after the meeting at Danane with the RUF external delegation.

He (Golley) had returned to London after that initial encounter, and had escalated his engagements with International Alert, the ICRC, the Commonwealth Secretariat, the UN, and occasionally, through telephone conversations, with members of the RUF he had met in Danane.

It didn’t take Ambassador Golley long, to learn that a meeting had been scheduled between the NPRC military government of Sierra Leone and the RUF.

In his quest to see a peaceful resolution of the conflict, as well as the realization that the forthcoming meeting would afford a wonderful opportunity for his Group (operating under the umbrella of the National Convention for Reconstruction and Development NCRD) to meet with Foday Sankoh and the RUF leadership, to continue the process of dialogue and also to encourage and support a sustainable peaceful resolution of the conflict, Ambassador Golley wasted little time, in mobilizing other members of his organisation, to travel with him to Yamoussoukro for this historic meeting.

He contacted Oluniyi Robbin-Coker, Osman Yansaneh, Lans Gberie, Ambrose Ganda, and other Sierra Leoneans, offering to meet the cost of the travel for the whole Group, from their respective departure points in the UK and West Africa, to join him in attending this upcoming meeting as Observers.

The Late Ambrose Ganda, penning details of the historic event, in his Focus on Sierra Leone in March 1996, wrote: “I arrived in Abidjan Sunday morning 24 March, determined to witness the historic meeting between Maada Bio and Foday Sankoh, but not knowing what the program of events was. I checked into my hotel room and was just about to steal a wink – having travelled on a night flight from London – when the telephone rang only for me to be told that both men were due to arrive in Yamoussoukro that very evening.”

Ambrose Ganda went on: ‘I hurriedly surrendered my keys at the reception and checked out. I was in the company of three compatriots – Omrie Golley, Chairman of the National Convention for Reconstruction and Development – which also paid for my trip as with an earlier visit, Mr Osman Yansaneh, a personal assistant of ex-President Momoh, who travelled from Conakry, and Mr Lans Gberie, editor of Expo Times, who had travelled from Freetown as an independent observer. We boarded a hired jeep, and headed with a rendez-vous with history, nearly 450 kilometres in the North of Ivory Coast.”

Ambassador Golley and his fellow compatriots arrived late that evening, finding accommodation at the same hotel where both the Government of Sierra Leone delegation, together with that of the RUF were residing, and sent word to both delegations, upon their arrival, that they had arrived to witness the historic event, expressing a desire to meet with them.

Golley and the rest of the group that accompanied him received immediate word from Foday Sankoh that he was very keen to meet with them.

Warmly welcoming Golley and his fellow Sierra Leoneans, Sankoh went on to berate Ambrose Ganda, in a friendly way, for some unflattering remarks Ganda had made months earlier about the RUF, in one of his publications which had been brought to his attention. Sankoh was equally swift on putting that episode aside, engaging the group in an informal manner.

Foday Sankoh, then went on to speak copiously about the reasons why the RUF had embarked on what he termed ‘an armed struggle’, and giving a lecture on what he termed the core of the thinking of the Movement – Pan Africanism- and the need for grass roots involvement in the political dispensation of Sierra Leone which he described as lacking.

Golley and Ganda in their own individual comments, mentioned to the RUF leader that they had come as independent observers to the peace meeting, not being part of any official delegation. Golley went on to add, that they would probably be waiting outside the hall – where the meeting was to take place – until it’s conclusion, and that the Group had come to Yamoussoukro to give moral and where necessary, practical support to both sides.

Sankoh’s immediate response was: “We are all Sierra Leoneans, aren’t we? We are here to talk about peace for our country. Every Sierra Leonean must be welcome! You do not need an invitation for that, do you? You should come to the hall tomorrow to make your presence felt.”

Golley remembered this initial encounter, and did not also forget an amusing moment in these auspicious surroundings: “We were all seated in the inner suite of Foday Sankoh’s quarters with Sankoh resplendent in traditional ronko attire, with us listening animatedly to him dilating on the reasons why the RUF took up arms. In the middle of this discourse, Sankoh got up suddenly to attend to a call of nature. Thinking that this brief departure and interlude, would afford the group a few minutes to compare notes on our individual feelings, we were surprised to witness Sankoh enter the bathroom, sit on the toilet seat, bathroom door ajar, continuing with his discourse, as if there was absolutely nothing wrong with this particular mode of engaging in public conversation.”

The scheduled peace talks eventually took place, the following morning, on Monday 25th March 1996. It was a historic meeting between the NPRC Leader and erstwhile Head of State, Brigadier Julius Maada Bio and the RUF Leade

This initial encounter was itself preceded by high drama, which Omrie Golley and his brethren had not expected or prepared for.

Just before the event itself started, one of the NPRC Delegates came into the Hall, and formally objected to the presence of Ambassador Golley’s group at the gathering, naming him in particular, stating that stated that he (Golley) and his team, were neither part of the government delegation, nor part of the RUF Delegation. The meeting stalled and escalated into a serious stalemate.

The RUF Delegation maintained that, as Sierra Leoneans, Golley and his Group, were perfectly entitled to remain as observers of the Meeting. The Government delegation on the hand argued that the NCRD team was not illegible to attend as they weren’t part of the official or RUF delegation.

“For my part, initially I dug my heels in, stating that as observers recognized by the hosts in the Ivory Coast, together with one of the participating Delegations who had insisted that we attend, we couldn’t simply leave the Hall because the Government Delegation objected’’

The Stalemate sadly continued, with the delegations maintaining their respective positions. Tempers flared. Golley continues: “The historic Meeting was on the verge of collapsing even before it started. One side, it seemed, had to back down or give in.”

It was however not long before Ambassador Golley relented, taking the view that his being singled out by one of the Parties to the peace talks, objecting to him and the Group witnessing the occasion, was a small price to pay, taking into account the reason why he was there in the first place – giving peace a chance, and doing everything possible to end the hostilities and bring about lasting and sustainable peace to Sierra Leone.

In our next article, we will discuss the Yamoussoukro meeting and the role played by Omrie Golley in arriving at an Accord.

Be the first to comment