Sierra Leone in 2007 passed innovative laws aimed at reinforcing women’s rights and clamping down on sexual violence, but as the government and social services struggle to implement the laws crimes against women remain rampant, officials say.

Sierra Leone in 2007 passed innovative laws aimed at reinforcing women’s rights and clamping down on sexual violence, but as the government and social services struggle to implement the laws crimes against women remain rampant, officials say.

Up to 67 percent of urban Sierra Leonean women were victims of domestic violence in 2011, Fatu Kargbo, a director in the Ministry of Social Welfare, Gender and Children’s Affairs (MSWBCA) told this medium.

Isha Bangura, director of the police Family Support Unit (FSU) – which receives most domestic abuse reports – said the most common domestic complaint they receive is physical violence.

“Most of the time women and girls are abused by people they know…[The perpetrators] are rarely strangers,” said Eunice Whenzle, who heads the Rainbo Centre, a counseling and treatment clinic for raped and battered women in the capital Freetown. “We also see cases of incest,” she said.

Rainbo Centre staff in the capital Freetown and in Koidu, Kailahun and Kenema are also seeing an increase in the number ofteenage girls pregnant from rape on the rise, Whenzle said.

The 2007 Gender Act included a bill making violence or sexual abuse against women, including within marriage, a criminal act. Government officials and NGOs IRIN spoke with agree the act marks progress, but they could cite no cases where it has been used to successfully prosecute violators.

This is partly because there are so few lawyers or judges. In eastern Sierra Leone’s Kenema district, one magistrate services 360,000 people. He processes eight cases a day and often has to gather his own evidence when police evidence is insufficient, according to Rainbo’s annual report.

Too often cases are dismissed before they enter a court at all, says the FSU’s Bangura. Rape cases require a medical certificate but this is difficult to obtain in a country with one doctor for every 18,000 people according to the World Health Organization. Referral systems between the police, health services and the courts are often unclear or not standardized, leaving many women confused, according Bangura.

The FSU cannot cope. “My unit is seriously under-resourced to cope with all the gender-based violence,” Bangura said. “The basic structures, including equipment to collect accurate data, are insufficient.”

Freetown’s Rainbo Centre clinic treats and follows up on 70 sexual abuse cases each day, according to Whenzle.

Families usually dissuade women and girls from reporting sexual violence, urging them to settle out of court or turn to “traditional justice”, said the MSWBCA’s Kargbo; this usually involves a discussion, payment and a ban on future contact.

This fosters impunity, she said. “If punitive action is not taken against violators of the gender act, incidences will continue unchecked.”

Coordination

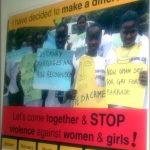

![]() Though lack of capacity remains a barrier, political will is mounting to reduce sexual violence, said FSU director Bangura.

Though lack of capacity remains a barrier, political will is mounting to reduce sexual violence, said FSU director Bangura.

The MSWBCA in 2011 set up a national committee, with NGO and UN agencies participating, to coordinate the fight against sexual violence.

“It [the committee] has been instrumental because it has brought all the other agencies working on gender-based violence together to make sure we’re all focusing in the same direction,” said the Rainbo Centre’s Whenzle.

To date committee members such as the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Rainbo Centre and other NGOs have helped facilitate referrals among police, doctors, lawyers and counselors and trained health workers in examinations for sexual violence and police in how to prosecute cases, said UNICEF’s child protection officer in Sierra Leone Rosina Conteh.

But real improvement requires a change in attitudes toward women, who have low status in Sierra Leone society, Whenzle said. With just one in four women able to read or write, many are unaware of their rights, she said. “The traditional perception in domestic [abuse] cases is that women should accept what is happening to them. We are trying to change that.”

Many blame violence on the civil war, which was notorious for its rape and attacks on civilians. But the government’s Kargbo said it goes back further. “Long before the war, violence [against women] has been the order of the day in both urban and rural areas.”

The media, traditional leaders, women’s activists, human rights groups and NGOs must work together to change attitudes, she said. “Making the gender law effective cannot happen overnight…it requires a long-term investment to change culturally-engrained practices.” She added: “The act took four years to pass through parliament, now we need more time to popularize it.”

Be the first to comment